This autumn, ECF highlights cultural policy research and activism in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Through a series of interviews, ECF introduces cultural activists from across the region who are working with us on developing and influencing cultural policy development in their countries (from Algeria and Egypt to Palestine and Lebanon). Some of their analysis and research contributes to the World CP – the International Cultural Policy Database – which, since its launch in 2015 by the International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies (IFACCA), is growing as an important monitoring tool of country-specific cultural policy reviews from around the world.

Rana Yazaji. Photo via Mimeta.

“The well-being of the artists, wherever they are located, is a priority for us. Unfortunately, we can’t help much in improving their status in their country of refuge. What we are trying to do is to promote these artists as professionals in the field, instead of tagging them as “refugee” artists, or “Syrian” artists. ”

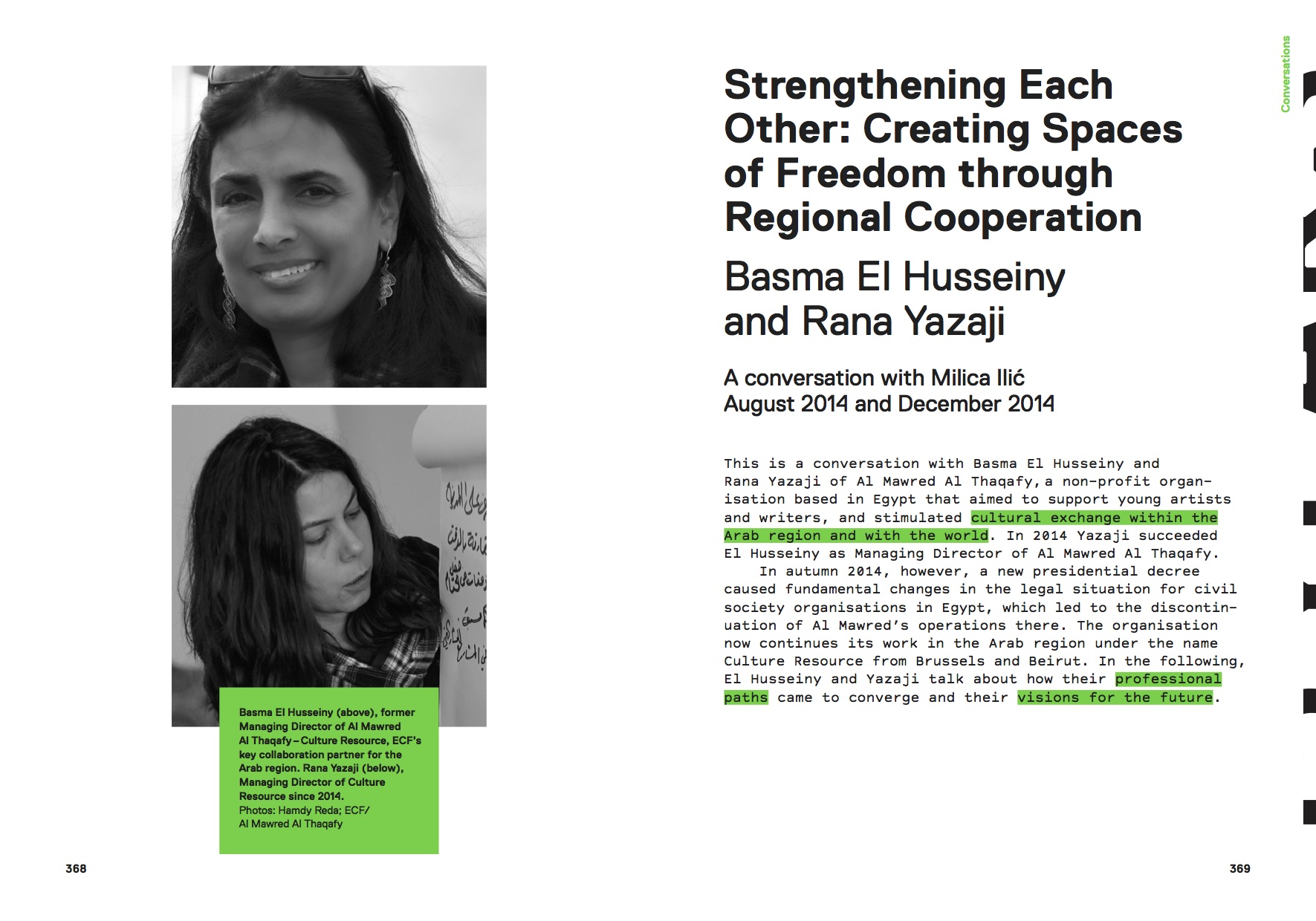

In this conversation, we talk to Rana Yazaji (Syria), Managing Director of Culture Resource (Al Mawred Al Thaqafy) – a key cultural player in the MENA region that facilitates the development of national cultural policy groups in more than ten Arab countries. We talk about her work and about the challenges she and her team face in these turbulent times for the region.

Rana Yazaji is an activist, researcher and programmer in the field of culture and cultural policies. She became the Managing Director of Culture Resource (Al Mawred Al Thaqafy) in 2014. Founded in Cairo, Culture Resource is among the most prominent non-profit organisations operating across the Arab region from its new base in Beirut, Lebanon. It supports the development of artists, cultural managers and cultural organisations through a wide range of programmes and services with the aim of encouraging the growth of the region’s independent cultural sector.

Rana is also a founding member of the Syrian cultural organisation Ettijahat. Independent Culture in Damascus, which has been coordinating ECF-supported civil society task forces for cultural policy analysis in eight Arab countries (the Arabic profiles of the World CP).

Apart from her work as a researcher, trainer and consultant in cultural and developmental projects and communal initiatives, Rana has worked as a cultural project manager and programme director for a number of institutions, such as the General Secretariat of Damascus Capital of Culture and the Cultural Project of the Syria Trust of Development (Rawafed).

Rana Yazaji, Director of Culture Resource (Cairo/Beirut/Brussels)

Rana, the last time you were interviewed for ECF was for the publication Another Europe in late 2014. You had just become the Managing Director of Culture Resource. A lot has happened in the region since then. Can you tell us what the most crucial events or changes were for your organisation and how it has impacted your work?

One month after I started in my position as Managing Director of Culture Resource foundation, we decided to move to Lebanon because of changes in the Egyptian law. For at least one year (between October 2014-2015) – as well as running all the programmes, trying to maintain our work and responding to the needs in the region – our focus was also on restructuring the organisation. Moving the foundation from Cairo to Beirut meant that we had to establish a new legal entity in Lebanon – a civil company to carry out the main activities of the foundation in the region. At the same time, we had to establish a new independent corporate entity in Egypt – to carry on our work in Egypt, including El Genaina Theatre, Spring Festival and the Al Darb Al Ahmar Arts School. Related to that, we had to develop new internal structure regulations and a new visual identity and communications platform, including a new website that will be launched soon.

How did this transition influence the main programmes and activities of the foundation?

The core mission of Culture Resource has not changed, but we changed our strategies. We carried out a thorough evaluation of the impact of two of our main programmes (the Cultural Policy Programme – existing since 2009, and the Abbara programme, which has existed since 2010). We had to change our strategy and re-define our objectives in order to make them more relevant for the new contexts in the Arab region since 2011.

A spread from the Another Europe book. You can download the conversation from ECF Labs.

What are the main challenges you face when working in the field of cultural policy in the Arab region?

- Political and social challenges – the wars in Syria, Libya and Yemen, which have caused regional turmoil and forced thousands to flee their countries and look for refuge in neighbouring countries or Europe; and increasing censorship and restrictions on freedom of expression that are now directly targeting the cultural sector.

- Institutional challenges – institutional frameworks and capacities in the region are not strong enough to support a strong cultural sector. We started working in 2011 on improving this situation through the Cultural Policy Programme. We will open a funding call in the autumn of 2016 with the aim of strengthening a number of existing independent structures in the region and enabling them to support the cultural sector better in their own environments. We focus on independent organisations (associations, foundations, networks etc., regional or national, which have established their activities and mission in the last five years).

- Limited resources for the arts in the region is a persistent issue, which we try to address via our different grant programmes.

What are Culture Resource’s most important programmes and areas of expertise? How are you creating increasing impact in the region through your work?

While we have been trying to keep all the foundation’s previous programmes running, we have had to respond to the emerging needs of the growing community of displaced artists and cultural managers who are spread across Turkey, Jordan, Europe and other places.

How do we respond? Supporting the international mobility of young artists from the Arab region to showcase their work globally was always our priority. However, we have also had to consider a different type of mobility, particularly the increasing number of artists and cultural managers who are being forced to flee their countries as a result of physical threats because of their work. Culture Resource will soon be launching a new international mobility programme, Kon Ma3a El Fann – which loosely translates to “support art” in English – to address this challenge.

Culture Resource has always focused on supporting a new generation of artists in the Arab region. We needed to adjust our programmes to the new situation, because by the time they were launched (2007 onwards), we were focused on developing “the grammar” of cultural policy knowledge in the region. Having laid the foundations of cultural policy knowledge and awareness across the cultural sector (not only in academia), the next stage is to build up capacities for stronger advocates for these policies.

The well-being of the artists, wherever they are located, is a priority for us. Unfortunately, we can’t help much in improving their status in their country of refuge. What we are trying to do is to promote these artists as professionals in the field, instead of tagging them as “refugee” artists, or “Syrian” artists. For example, we recently organised a talk in Germany with Arab artists who had moved to Germany. They all talked about the stereotypical, often patronising approach of institutions and cultural organisations towards them. They were not being addressed as part of a new social fabric that is being created in some European cities – something they could truly contribute to with their knowledge and skills. We would like to contribute to a stronger engagement and more profound debate, rather than “organising another event for Syrian artists”. We are trying to help promote their work as artists where they are located, and to facilitate their integration in the new realm.

We target both artists in exile, as well as those who have stayed in their countries and in the Arab region. Artists and cultural operators in exile have lost a lot: starting from their level of communication, as many often don’t speak the language of their host country; the loss of their professional network and working environment; lack of knowledge about the rules and opportunities to help them function professionally; lack of awareness of their rights; how to find funding; how to reach new audiences etc. It may take a long time for them to reconstitute fully as professionals and to create new social networks.

We address artists at risk – those who are still in the region – with programmes aimed at sustaining their work in their countries. We are trying to find ways to help them operate in the region and fulfil their mission now and for the future – until the wars or turmoil hopefully settle down. This is really difficult, because national governments are not supportive of arts and culture. For example, an artist from Yemen cannot stay legally in Jordan, but people are forced to flee because of the ongoing war. In Jordan they have to pay a daily due just to stay safe but illegally, and there is no chance to achieve any legal status at all. We are trying to help these artists to become agents of change in their region and the above-mentioned programme Kon Ma3a El Fann targets them in particular.

Regarding censorship and political oppression, we are trying to support cultural operators to stay in the region (not necessarily in their own countries), to keep their activities running and to continue their work. If we don’t, the civil society movements and the resistance will be lost. There are 24 countries in the region with common needs but also very specific situations, so there is a lot of diversity to address.

Cultural Policy for All Egyptians campaign. Photo by Hamdy Reda.

What are the areas where you think Culture Resource could have the strongest impact? And which areas are you most proud of?

Cultural Policy Programme – one of the most difficult ones, but still one of the most important long-term programmes of the organisation.

In the current state of political turmoil and democratic setbacks in the region – directly affecting the safety, welfare and work environment of artists, cultural institutions and art groups – the idea to develop and support work on culture policy in Arab countries in the region is no longer an option. It is inextricably linked to our existence. Many strong and important outputs and outcomes could materialise through this programme.

For example, the Algerian National Cultural Policy Group (NCPG) currently has more than 40 members from different regions of Algeria. In 2013, they published a 14-chapter document, entitled Project of Cultural Policy for Algeria – their proposed version of a cultural policy.

The first national cultural policy group in the region, the Egyptian Group, organised Cultural policy for all Egyptians, a three-stage campaign that started in 2012. It promoted the idea of public access to culture through a wide variety of tools, including postcards, posters, ads on public buses, TV spots and a short film. The effectiveness of this project was found in the repetition and replication of the campaign’s slogans throughout the region.

The Sudanese National Cultural Policy Group also launched a campaign against racial prejudices and promoting the acceptance of racial diversity. The group developed seven activities for this campaign that focused on fighting racial discrimination, engaging in educational activities, changes in law, public activities related to media and art practices against war.

The National Cultural Policy Group in Yemen produced a booklet, General Framework for National Cultural Policy, highlighting the main outcomes of a conference organised in May 2013 by the Yemeni Ministry of Culture. The group transformed the conference’s recommendations into policy instruments, which the then transitional Yemeni Government approved and adopted. However, unfortunately, the current political situation has created an enormous obstacle to the development of the group’s work.

In its pursuit of providing a database and a platform to connect cultural policy operators and players in the region, Culture Resource created the website, Cultural Policy in the Arab Region, in collaboration with Ettijahat. Independent Culture. Since its launch in July 2014, the website has been collecting, archiving and displaying dozens of reports and news on activities and developments related to cultural policy in the Arab region. The website also features a database of related cultural activists and organisations.

Institutional support – we could do a lot to contribute to the knowledge and sustainability gap. The Abbara programme has achieved very good results, having worked with 48 organisations in the region, strengthened their capacities and made them more sustainable in the changing environment. The aim is that the participants will become responsible organisations that are in touch with the sector, sensing the needs and responding to them adequately. Cultural agents from the Arab countries need to be recognised strongly as part of the international knowledge networks – across Europe and globally.

Here are a few testimonies from participants in the programme:

- Thala Association for Reality Theare (Tunis): “We applied for a grant and our voyage took a new turn. The grant was not just about material support; it was about an organisational overhaul as the programme aims to transform its participant organisations into clearly structured institutions with precisely defined roles and functions.” For them this experience also expanded opportunities for regional collaborations in theatre co-production.

- Working with the Syrian filmmaker Orwa Al Mokdad, who produced the film 300 Miles about the siege of Aleppo (selected for the festival in Locarno in 2016). The author commented on Abbara: “For our film to be included in the activities of Culture Resource was a part of our aspiration to become part of the larger Arab cultural scene as our outlooks in the project are inseparable from the realities that we all experience in this region.”

- Basement Foundation (Yemen) said: “In circumstances such as those in Yemen, Basement was at risk of having its activities halted if it did not belong to a certain political affiliation or boycotted if it was identified with the ‘other side’ […] What our organisation gained from the Abbara programme was cultural management training, a greater facility in formulating and refining ideas, more professional management leading to greater efficacy, the ability to identify our goals precisely and realistically and to define ourselves concisely and innovatively, and the insights we gained into the successful experiences elsewhere in the Arab region […].”

You were at the forefront of setting up Tandem Shaml in 2012, a project of the Tandem Cultural Managers Exchange, which supports experimental collaborations between cultural change-makers from the Arab region and Europe and establishes cross-border cooperation links. Culture Resource still co-organises this exchange programme, which is currently running its third edition. What was the impact and the main value from this programme?

- Internationalisation of the artists’ work – exposing culture and arts from Arab region internationally. Tandem Shaml was the first programme where we focused on widening international networks for Arab cultural organisations and for individuals.

- Tajwaal is the mobility programme of Culture Resource.

- Building knowledge internally and in the region, but also expanding that knowledge and raising awareness about the region internationally: for example, the opportunity to collaborate with IFACCA on World CP and to have the chance to be part of the World Summit for Arts and Culture 2016 (Valetta, Malta).

- Strategies on reaching out to other international partners, expanding the opportunities for our beneficiaries and strengthening their resilience.

Cultural Policy for All Egyptians campaign. Photo via Culture Resource.

Culture Resource and Ettijahat work on the World CP, building a database of cultural policy for the Arab region, expanding your network from a regional to a global level. You work with advocacy groups in ten Arab countries to coordinate and support the development of transparent and democratic cultural policy in their countries, which is then made available to an international audience. What do you hope to achieve with your work in the long term?

Illustrating the impact of the Cultural Policy Programme of Culture Resource (launched in 2009 in collaboration with ECF and DOEN Foundation). Where are we now, compared to the start?

My own story with this programme started in 2009, when I was one of the researchers who applied to take part in the programme to develop cultural policy reviews of eight Arab countries. I was selected to research the cultural policy of my own country – Syria. This was my first interaction with Culture Resource. When we first gathered for the training, we had all acknowledged our knowledge in the field, but with very few exceptions, none of us considered him/herself a “cultural policy researcher”. We started discovering what cultural policy research meant. As a part of the cultural policy group in Syria, I had to explain to artists and cultural organisations the basic concepts of cultural policies, in order to get them on board for advocacy.

Culture Resource was the first organisation in the region that opened a call to support regional cultural policy initiatives. There is a variety of them – from the public to the independent sector. When compared to 2009, there is clearly more awareness today – both from a practical and academic point of view – about the raison d’être of cultural policy making and research.

Although chances for the independent sector to influence cultural policy decisions are rare even today in many countries in the region, we believe that this cumulative process developed since 2009 (now engaging more than 200 people, which is the number of members of CP groups!) will continue to bear fruit. We are trying to work both “bottom-up” as well as “top-down” (whenever possible), to get there.

'Shaml' is the arabic word for 'getting together'. Tandem/Shaml is a platform for cultural managers to exactly do this: bring people together. Photo by Constanze Flamme from a recent Tandem Shaml meeting in Jordan.

What is the effect of the peer-to-peer exchange among the countries and the CP groups in the region?

The most important thing is that exchange is happening, albeit with different levels of intensity around diverse issues, but it is there, despite the difficulties in their mobility across borders sometimes. With Ettijahat, we are organising one annual meeting of the cultural policy groups from the 12 countries we work with now.

Through the dedicated website www.arabcp.org we are trying, with Ettijahat, to share country specific knowledge and the new dynamics – via the newsletter and regular updates on the website. We are looking forward to extending our network and database of cultural policy researchers and stakeholders.

From 18-21 October, Rana Yazaji and Abdullah Al Kafri are taking part in the 7th IFACCA World Summit for Arts and Culture in Valetta, Malta. Here they will meet with the largest global network of arts councils and cultural agencies.

Further reading from the ECF Library:

- Syrian Culture in Turbulent Times – an article by Rana Yazaji & Nadia von Maltzahn in Another Europe.

- Cultural Policies in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria and Tunisia - An Introduction – Boekmanstudies, Culture Resource (Al Mawred Al Thaqafy) and ECF, Amsterdam, 2010 in partnership with DOEN Foundation and British Council (Lebanon).

For recent news on Arab Cultural Policies in Arabic and English, please visit www.arabcp.org